Longread AJJIT

A rehearsal for life otherwise

Khadija El Kharraz Alami on ‘AJJIT’

With AJJIT, Khadija El Kharraz Alami explores how music, rhythm, and movement can spark a different kind of storytelling. In dialogue with artist and music producer Reda Senhaji, she delves into the polyrhythms of Moroccan music genres such as Ahwach, Gnaoua, and Chaabi. Manal Benmalek spoke with Khadija a few weeks before the premiere.

It begins with a low pulse, steady as a heartbeat. Each repetition deepens the call, and the sound spreads like breath across the room. AJJIT – meaning ‘to let go’ in Tashelhit, an Amazigh dialect spoken in southwestern Morocco – is less a performance than a state of being. Entering its space, you don’t step into a theatre so much as into a process that has already begun, a pulse that is older than the room and that will outlast the night. What it stages is not a fiction but an experiment in time itself: how to awaken a body dulled by the pace of the present, and re-align it with rhythms that are deeper, stranger, harder to contain.

For Khadija El Kharraz Alami, theatre is never only theatre. Her work has long unsettled the boundaries of stage and ritual, stripping open spaces where vulnerability and intensity can gather without the filter of convention, actively disrupting the formal rules that often govern contemporary performance. She speaks of “awakening our pre-capitalist bodies”, an idea drawn from Silvia Federici and that resonates more like an invocation than a theory: beneath our everyday gestures, beneath the speed of screens and the suffocating tick of schedules, there remain older patterns of breathing, older ways of standing together. That resistance lives in the body itself, in movements, gestures, and rhythms that refuse the logic of our current capitalist time, and AJJIT sets out to make those patterns audible again.

Here, sound is the primary medium, but it arrives through the body before it lands in the heart. The ground is set by a single gesture, a hand clapping a beat, a voice leaning into a repeated phrase. In Moroccan traditions like Gnawa, Ahwash, or Issawa, this is how a ceremony begins: rhythm is laid down not as backdrop, but as vehicle, the carrier of trance. Once the body locks into it, once the cycle takes hold, the self begins to loosen. The jnoun – or spirits, forces, presences – are invited in, not as superstition, but as a way of letting go, or of AJJIT.

From here, Khadija works with gestures and pulses that unsettle and move outside the usual measures of time. Alongside her, Reda Senhaji, as Cheb Runner, carries those legacies into circuitry. His tools – the Digitakt with its flashing grid, the modular synthesizer with its riot of coloured patch cables – are never just technical. The tangle of cables echoes the seven colours of a Lila, the all-night Gnawa ceremony where each shade signals a presence: white for the saints, pale blue for water, dark blue for air, red for blood, green for masculine spirits, and yellow for feminine ones. In the ritual, cloth and colour guide the movement of trance; here, Reda’s cables seem to serve as similar cues, signals of invocation. Layered with voices and hand percussion, his machines don’t mimic ritual but extend it into the language of the present. The process isn’t smooth. Traditional polyrhythms don’t sit easily inside the machine’s binary grids. A six-beat cycle trips over a sequencer built for four; accents slip, silences fall out of place. But this friction is the work. He bends the hardware, splits patterns across channels, staggers sequences until the loop begins to sway against its own framework.

What emerges is craft in its most tactile sense: a patient negotiation with material, shaped by repetition and close listening. Each misaligned beat becomes part of the texture, each adjustment a dialogue with the machine. The aim is not to impose order but to let rhythm breathe inside the circuits. The process feels painterly. Reda lays sounds as if they were pigments: voices from friends, samples from old keyboards, live textures bent and re-shaped. Some are blurred with delay or distortion, others left raw like brushstrokes on rough canvas. Each patch on the modular is a new palette, a shifting balance of tones. Just as a painter might return to the same subject with new pigments, he revisits the same cycle with new timbres, adjusting to keep the image alive and breathing.

If there is a ghost in Reda’s machines, it isn’t technological but ancestral. The loops don’t simply repeat, they summon. Each cycle marks a threshold, each texture a presence. The jnoun hover not as exotic folklore but as a reminder of how sound can open us, how repetition can draw out what is hidden, how trance can dissolve the barriers of the self.

Khadija’s presence is different but entwined. She inhabits the stage as a facilitator. The performance resists the kind of hierarchy that isolates or dominates. If hierarchy exists here, it is one of care: a structure that holds the group, that orients toward community rather than control. The performer and the audience share the same air, moving and listening together until the line between them begins to dissolve. What emerges is closer to ritual than to spectacle. The stage is a site of gathering, the sound an offering, the audience a living assembly bound by rhythm.

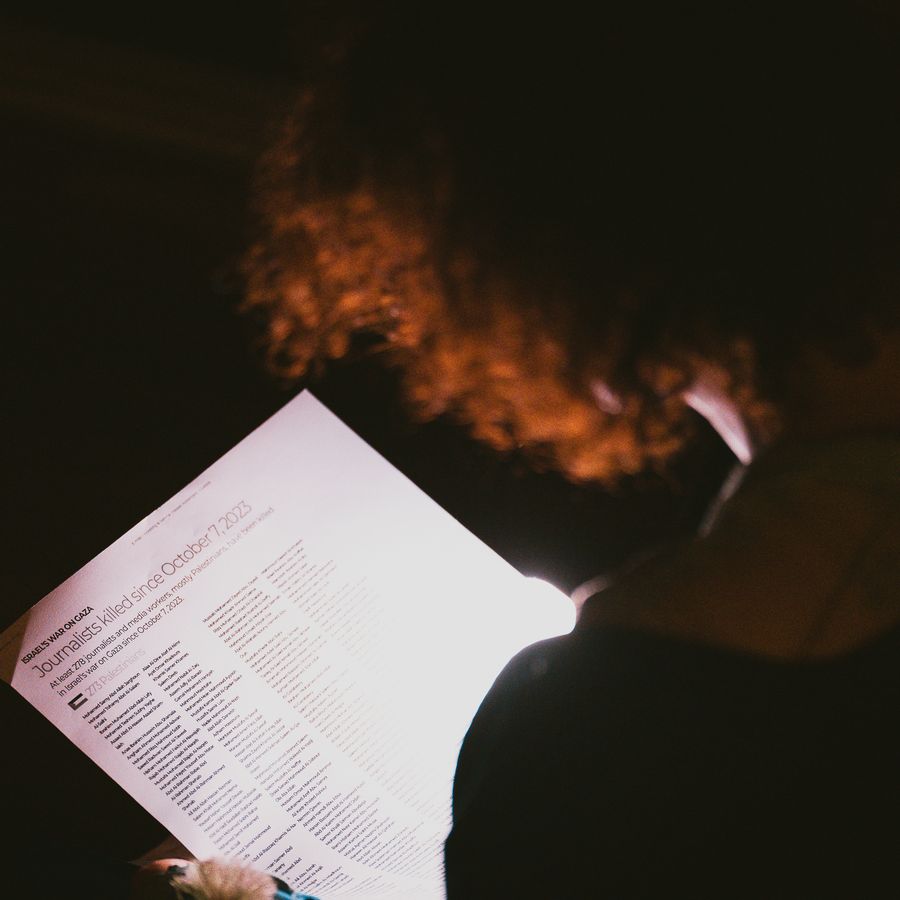

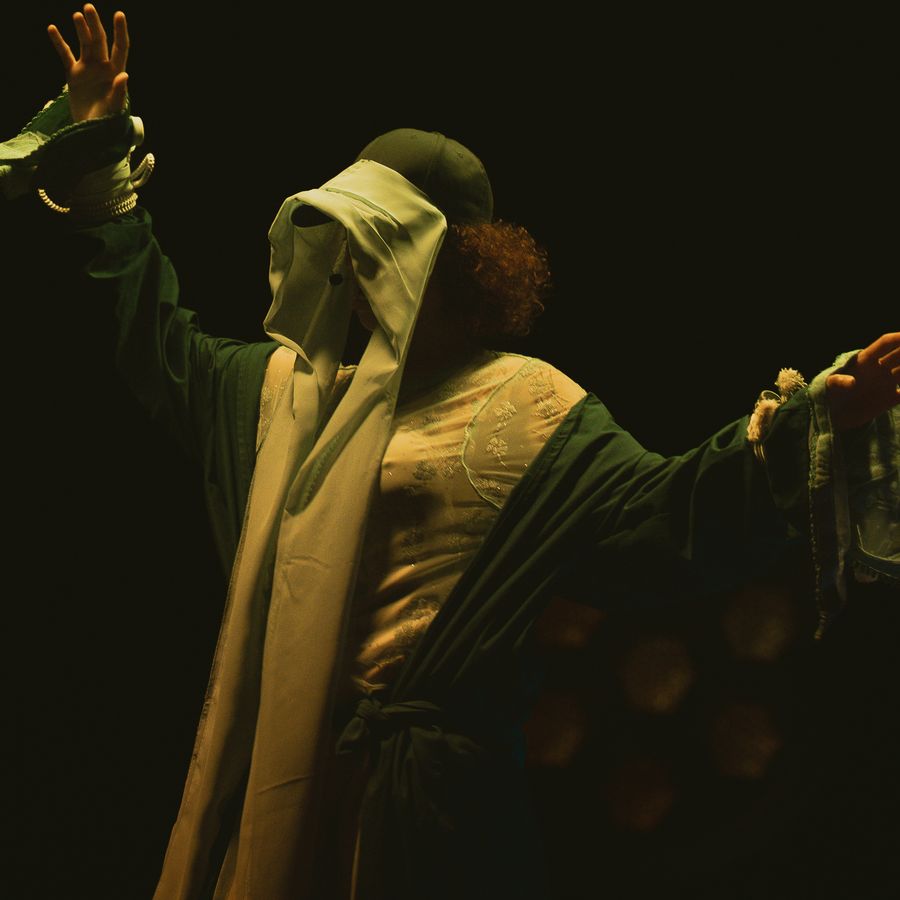

The trance-state is central. In Gnawa ceremonies, trance is not escapism but healing; it allows the body to face its jnoun, to dance with them, to acknowledge them, and in doing so, to reconcile with what disturbs it. AJJIT works with that principle, but through theatre and electronics. Reda becomes the Maalem, the master of ceremony, guiding the room with music. Khadija embodies the cheikha, the dancer-entertainer who lives without boundaries, always ready to surrender to rhythm. At the same time, she carries the trace of Lalla Mira, the spirit tied to yellow, to joy, to the insistence of dance. She takes the microphone, singing in repetition, her face at times veiled. In North African celebrations, veils are not fixed in meaning: sometimes modesty, sometimes disguise, sometimes permission to cross into altered states. Here, it is a way to fully let go. Between these two figures, she channels freedom, intensity, and the unpredictable energy of the ritual, calling for the jnoun while shaping the audience’s experience through voice, movement, and pulse. Within this, the consciousness of the room loosens and listening becomes a shared, almost otherworldly practice.

This is where the project brushes against something larger than itself. In a world where our sense of time is relentlessly broken down into tasks, deadlines, and notifications, to enter a trance is already resistance. To let rhythm guide you rather than algorithm is to remember another temporality, one that capitalism cannot capture or reproduce. The ceremony offers a rehearsal for life otherwise: a slowing down, a realignment, a reminder that time can be circular, expansive, porous.

Khadija’s theatre background grounds the work in presence. Her earlier pieces blurred autobiography and myth, public and private, stage and street. AJJIT unfolds within her format of “performative research performance”, first explored in RE-CLAIMING SPACE, where the stage becomes a space to test and remake how bodies inhabit it. She moves as host and participant, guiding the room while surrendering to it. She steps inside the process, risking altered states and exposing herself to what arises. Vulnerability is not symbolic: it is lived. It’s a way of letting the performance work on her as much as she shapes it.

Together, Khadija and Reda create a field where sound, gesture, and memory intersect. Machines carry ancestral rhythms, bodies generate frequencies that resonate inside the hardware, voices trace echoes of prayers and invocations. The ritual is not a symbol but a condition, constructed in real time by everyone present.

AJJIT does not aim to reconstruct tradition, nor to modernise it. It treats tradition as a living archive, something to be activated rather than preserved. The polyrhythms of Gnawa, the collective force of Issawa, the ceremonial spaces of indigenous North African practices: these are not aesthetic references but practical tools, techniques for generating states, for reawakening bodies. By weaving them with electronics and theatre, the work does not dilute them but extends their reach, opening new pathways for them to act.

Stemming from BLUEPRINTS, AJJIT also gestures towards SHRINE, its larger counterpart. If AJJIT is the experiment, then SHRINE is the construction of a full environment. There, the ceremonial aspects will expand: soundscapes, chants, and architectural presence shaping a total immersion. But already in AJJIT, the seeds are clear: the importance of sound as a portal, and ritual as our mother technology.

What remains after the performance is not simply memory of a show, but a bodily trace: the echo of rhythm in the chest, the sense of time stretched and unsettled, the faint afterimage of a collective state briefly entered. This is its politics as much as its poetics. In an era where every moment is measured and monetised, to lose oneself in rhythm, to encounter one’s jnoun, to awaken pre-colonial memory: this is a small act of liberation, a reminder that other ways of being together are still possible.

Manal Benmalek